Hypersomnolence: Is there such a thing as too much sleep?

Hypersomnolence , or feeling tired all the time despite having adequate sleep at night, can be problematic for anyone who needs to stay awake and alert during the day.

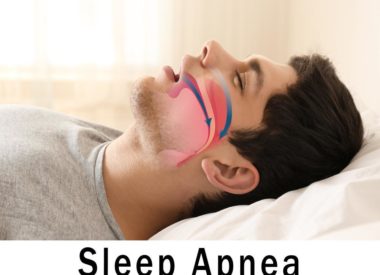

While sometimes the causes of hypersomnolence are clear going to bed too late and waking up too early, having a sleep disorder, practicing poor sleep hygiene, or experiencing adverse effects of a medication some people seem to naturally sleep longer.

But is so-called “long sleep” considered healthy? And if not, what are the risks?

What is long sleep?

This term describes people whose natural sleep-wake cycles tend to call for more sleep than others in their age group, according to the American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM). These people regularly sleep 10 to 12 hours every night, and their sleep is usually of good quality. Their biggest complaint may be that the day is not long enough for them, because they routinely spend an extra 2 to 4 hours asleep, compared to their peers.

(In contrast, a “short sleeper” typically feels well rested on just 6 hours of sleep every night.)

Is long sleep healthy?

It depends entirely on the individual. If they are getting good quality sleep, have sound sleep architecture, and are otherwise healthy, then it’s probably not a health concern as much as an inconvenience.

Much like the reality for those with other sleep disorders (in example, delayed sleep phase disorder or idiopathic hypersomnia ), some long sleepers struggle with jobs and relationships because their sleep schedules can create stress and disrupt social lives not only for them, but also their loved ones.

Long sleepers may also routinely medicate with stimulants if they are to maintain schedules that don’t allow them to sleep for their preferred duration.

Is this long sleep, or hypersomnolence caused by sleep deprivation?

From the June 2016 edition of Sleep Health : “Epidemiological studies consistently show a strong U-shaped association between sleep duration and health outcomes. That is, both short and long sleepers are exposed to greater risks of death and diseases than normal length sleepers.”

The article’s authors share that one possible explanation is that long sleep may not just be a genetic preference or circadian marker, but evidence of “poor sleep quality or some unmeasured risk factor” which associates long habitual sleep with poor health.

Sleep deprivation may, in fact, be the unnamed villain here. Sometimes, people who believe they are “long sleepers” are actually normal sleepers who have become sleep deprived (for whatever reason). Lost sleep consolidates over time to create sleep debt, which can be difficult to reconcile if left unaddressed; for some, sleep debt may never be paid down.

Hypersomnolence could also be a result of sleep deprivation caused by underlying (and/or untreated) health conditions, undetected sleep disorders, medication side effects, or poor sleep hygiene. Other outcomes of sleep deprivation:

-

Long periods of REM sleep or “REM rebound”

-

Oversleeping if left to “sleep in” (without an alarm)

These kinds of long sleep duration are also hallmarks of sleep deprivation and may not be attributed to natural rhythms of long sleep.

How much sleep is enough?

The National Sleep Foundation updated its recommendations for adequate sleep in 2015 to reflect the needs of specific age groups. Most adults need an average of 8hours of sleep every night. Any deviation from this norm can be cause for concern as recent studies have shown that too much sleep (as well as too little) can lead to chronic health problems.

These problems include diabetes, depression, stroke, and heart disease.

Diabetes and long sleep

March 2016 research published in the Annals of Medicine suggests that “both long sleep duration and afternoon napping were independently and jointly associated with higher risk of incident diabetes” in middle-aged and older subjects in a study in China.

Another cross-sectional study published in Circulation earlier this year showed that Hispanic individuals who slept greater than9 hours showed less control over their glycemic status than those who slept fewer hours.

Mood disorders and long sleep

For a decade, studies published in SLEEP suggest ongoing statistical links between depression, long sleep, and mortality.

More recently, a study of twins in2014 revealed a 50 percent higher chance of developing depression for those sleeping10 or more hours nightly.

Both short and excessively long sleep durations appear to activate genes related to depressive symptoms, said Dr. NathanielWatson, AASM president and the study’s principle investigator.

Yet another study in Journal of Clinical Psychiatry showed that long sleepers were more than 2.5 times more likely to suffer from persistent depression and anxiety even after adjusting for psychiatric symptoms.

Vascular risks and long sleep

Stroke risk increases for those with persistent long sleep, according to data compiled in a study published in Neurology in 2015.

Long sleepers faced a 46 percent increase in both fatal and nonfatal stroke after adjusting for cardiovascular factors and other health conditions.

More recently, a study of elderly Japanese people with hypertension showed that those who slept more than 8 hours a night were more likely to experience stroke when compared against those who slept just 8 hours.

Cardiac problems and long sleep

A very large cohort study published in The International Journal of Cardiology shows that those who sleep more than 8 hours nightly are at 35 percent higher risk for dying from coronary heart disease.

A previous 2012 study using data from theNational Health and Nutrition Examination Survey also found that those sleeping more than 8 hours a night are twice as likely to suffer from angina and have increased risks for developing coronary artery disease.

Should you be concerned?

Other studies show correlations with other chronic illnesses and health concerns for those with persistent long sleep habits, such as obesity and accelerated cognitive decline. Research continues to search out reasons for why sleeping more than 8 hours a night leads to chronic disease and advanced mortality.

Do you sleep more than 8 hours a night? You might ask yourself why. While some natural “long sleepers” may do just fine with this persistent excessive sleep habit, the risks that come with sleeping long are hardly something to ignore.

If you have concerns, you are encouraged to discuss these with your primary care physician. It can be difficult to distinguish between “long sleep” and hypersomnolence by other causes without the help of a medical professional.

Or, if you’re unsure, tryout our free sleep health test below.

Sources:

American Academy of Sleep Medicine

American Journal of Epidemiology

American Sleep Association

Annals of Medicine

Circulation

International Journal of Cardiology

Journal of the American Society of Hypertension

Journal of Clinical Psychiatry

National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey

National Sleep Foundation

Neurology

SLEEP

Sleep Health