Sleep Apnea, Opioid Pain Medication, and the Sleep Study

Chronic pain is the enemy of sleep. It leads to sleep complaints for an estimated 28 million Americans. At the same time, millions also suffer from another chronic problem: sleep apnea. Doubtless, because of the sheer numbers of people experiencing these problems, there will be crossover between these two patient populations.

Add to the equation a third variable the use of opioid pain medications to treat chronic pain and things get even more complicated. Patients who struggle with both pain and sleep apnea may be using opioids to treat one issue… while unwittingly exacerbating the other.

And what about those who are living with undiagnosed and therefore untreated sleep apnea?

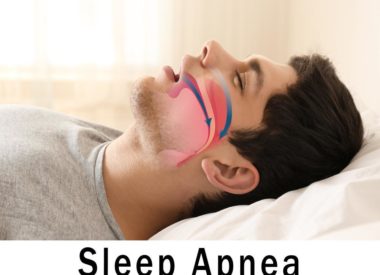

Let’s take a closer look at the enemy.

Pain and sleep architecture

People in chronic pain (such as those with rheumatoid arthritis or fibromyalgia), experience regular fragmentation of their sleep cycles, which deteriorates overall sleep quality and leads to broken sleep architecture.

Slow-wave sleep and REM cycles, the critical stages of sleep which help the body to manage inflammation and cellular restoration, may be lost entirely to nights of sleep eroded by micro arousals. These are patterns of alpha-wave “intrusion” which break up stable sleep, allowing only the more shallow stages of sleep to occur.

Lost sleep turns into sleep deprivation, and sleep deprivation is known to reduce the pain threshold, making pain even harder to tolerate. This vicious cycle is what makes it so hard for people to get the healing sleep they need.

How do opioid pain medications impact the respiratory system?

Using opioid pain medications has become a popular solution for the treatment of chronic pain. However, respiratory physiology is markedly changed while a patient is on a course of opioids.

- Central respiratory patterns are blunted

- Respiratory rate are depressed

- Tidal volume decreases

- Airway resistance increases

- Upper airway patency is reduced

All of these changes have the potential to develop into irregular ventilation patterns if ignored. Pauses and gasping from episodes of untreated sleep apnea can lead to even more unstable patterns of ataxic breathing (or Biots respiration). These kinds of serious respiratory problems are a common development in those who’ve been taking opioid pain medications over a long period.

Opioid pain medications and sleep apnea

Could using opioids cause sleep apnea? It’s hard to say, but studies have confirmed that using them in both the short and long term can contribute to the development of sleep apnea.

Traditionally, it was thought that using these medications led to instances of apneas caused by central dysfunction central sleep apnea syndrome (CSAS). The blunted messaging between the brain and the respiratory system during sleep, and while under the influence of opioids, has been well understood as a side effect of using opioids.

However, more recent studies have shown different results. For some long-term opioid users, CSAS did not define their sleep-disordered breathing (SDB), but obstructive sleep apnea (OSA). Opioids, which deeply relax the tissues of the upper airway, can potentially cause mechanical obstructions to take place. Left untreated, they could lead to severe respiratory problems.

Both cases of SDB have been observed in opioid users, making it critical that physicians more carefully isolate the root cause of a given patients SDB if they are also using opioids for pain management. Knowing the root cause will best inform future treatment strategies for these patients.

Treating opioid-induced SDB

Patients with sleep problems who are also using opioids for pain may benefit from a sleep study to identify any unusual brain wave patterns that could suggest a central impact on their sleep architecture as well as diagnose preexisting, but untreated or unrecognized, SDB. Treating sleep apnea can provide relief for these patients not only by helping to control breathing irregularities but also by helping improve their pain thresholds through careful treatment so that they might better manage their pain.

The gold standard for treating sleep apnea continues to be positive airway pressure (PAP) therapy, though for some cases of mild OSA where PAP is not tolerated, oral appliance therapy may also be useful.

Continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) is best suited for the pain patient with OSA, while those with CSAS usually fare better using a bilevel positive airway pressure (BiPAP) delivery system.

Opioids and polysomnography

Concerns arise, however, when a pain patient enters the sleep clinic for an overnight polysomnography. Their use of opioids will be evidenced in their test by the presence of specific alpha wave patterns during slow-wave sleep, illustrating the characteristic “imprints”these drugs make on sleep architecture. This could interfere with the accuracy of a study where other sleep disorders may be suspected.

A physician may decide to taper a patient from opioids prior to a sleep study to get a more accurate portrait of that patient’s sleep architecture and to see how much of their sleep disruption is caused by pain itself or by an occult sleep disorder useful information for making a treatment plan.

Discontinuing opioid use

For patients and doctors looking for motivation to revisit their therapy strategies, it’s worth noting that:

- If opioid use is discontinued, some residual sleep fragmentation may persist afterward; however,

- Some cases of SDB may improve or even resolve once opioids are discontinued.

The increased use of opioids for long-term chronic pain management is not going away any time soon. It’s critical that physicians keep in mind the impact these drugs may have on their patients respiratory systems as they sleep. Screening pain patients for undiagnosed cases of SDB or to uncover sleep apnea acquired as a result of opioid use may be key to helping these patients enjoy improved pain management, quality of life, and health outcomes overall.

Here at Sound Sleep Health, we aim to give pain patients the best chance for achieving better sleep.We have 3 locations in the greater Seattle/Kirkland areas. We hope you’ll reach out to us with your sleep health concerns.